José Mariano Gago

Este sítio da internet surge no âmbito de um movimento espontâneo da comunidade científica em Portugal.

Partilhe um testemunho sobre José Mariano Gago e o seu legado para o desenvolvimento do conhecimento, da ciência e tecnologia e da cultura científica na nossa sociedade.

Se tem fotografias que nos mostram como foi a acção de José Mariano Gago, memórias que queira partilhar, simples frases que melhor ajudem a documentar o seu legado de pensador e humanista, não hesite em partilhar todo esse material aqui.

Pode usar o endereço memoria@marianogago.org ou o formulário.

Use a hashtag #marianogago para partilhar nas redes sociais.

Os materiais enviados para este sítio são de domínio público

This website is born from a spontaneous movement of the scientific community in Portugal.

Share your memory of Jose Mariano Gago and his unique legacy and dedication to science and scientific culture.

Share here, on this website, your images and thoughts to help us document his life and work.

Send us an email to memoria@marianogago.org or use the following form

Use #marianogago hastag to share in social networks.

All the content received and published in this website belongs to the public domain

TESTEMUNHOS

Intervenção do Mariano Gago em vídeo no Centenário da U.Porto

Um vídeo de domínio público com a intervenção do Professor Mariano Gago na cerimónia do centenário da Universidade do Porto.

Jorge M. Gonçalves, Universidade do Porto

"Notas Bárbaras (quase diário)"

12 de Abril de 2014

O José Mariano Gago esteve três dias por aqui. Estava interessado em conhecer a universidade por dentro, particularmente nalgumas áreas para ele mais directas, e organizei-lhe um plano. Palestrou no Program in Science and Technology Studies, almoçámos com professores de ciências e jantámos com alunos. Levei-o a uma conversa na TV, tomámos muitos cafés (ele toma quatro de manhã e quatro à tarde) e, na quinta-feira, fomos num passeio de seis horas até Newport, que deu para abundante falatar.

Dá de facto gosto entabular conversa com ele. Contudo, não é para lhe tecer uma apologia que aqui venho. Não deixo, porém, de registar que, depois de duas passagens pelo Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia, não tenho qualquer notícia de ele estar agora a usufruir das avenças do proverbial tacho que se segue a uma jubilação ministerial. O que merece registo.

Falou muito das alterações no país no domínio do acesso à pós-graduação que, graças às bolsas do Ministério da Ciência através da FCT, tinham permitido a gente sem nenhum passado universitário fazer brilhantes carrreiras na investigação. Como exemplos, contou-me com justificado regozijo ter há tempos em Lisboa por mero acaso viajado no carro de um taxista que o reconhecera e lhe falara entusiasmado da sua filha, em tempos bolseira da FCT, mas agora nos EUA integrada num centro de investigação de uma excelente universidade da Costa Leste. Tudo isso, segundo o taxista, impossível de acontecer antes da entrada do seu cliente-passageiro para o Ministério e por isso lhe estava profundamente grato.

Deixei-lhe contar a história que com a justificada satisfação narrava, e acrescentei: Olha que quase aposto vais conhecê-la logo ao jantar e depois ao serão em minha casa.

Inibiam-me algumas dúvidas, mas tinha quase a certeza. Chegada, porém, a altura, eu sem querer ser directo a fazer a pergunta. Mas nem foi preciso porque, a propósito de já não sei quê, logo a filha do taxista, agora na Brown a fazer investigação num pós-doc em ciências cognitivas, puxou da conversa e pôs-se a falar com orgulho do pai, taxista em Lisboa, que até deixara tudo para ir à sua festa de doutoramento em Nova Iorque.

O José Mariano Gago dobrou o sorriso de contente. Alguma coisa tamgível resultara do seu empenho na transformação de Portugal. E estava alia o vivo, num casualíssimo momento permitido por este small world, piccolo mondo do universo lusófono.

Onesimo Almeida, Escritor e Professor na Brown University

Formação avançada - Arrábida 2013

Completou hoje, faz um ano, o desaparecimento físico de um dos homens da ciência que conheço pessoalmente e que continuarei a nutrir sempre admiração:

- Mariano Gago.

Narciso Gomes

Faz hoje um ano que Mariano Gago partiu, deixando-nos gratas recordações até sempre!. Conheci-lhe menos o lado científico, mais o humanístico que creio teria sido a sua próxima grande tarefa ... compreender Portugal, significava também compreender os seus momentos de intolerância como a que levou à perseguição de cientistas e dos judeus no Sec XVI. Nova Iorque e a comunidade sefardita de origem portuguesa que cedo aqui se instalou teria estado nos seus horizontes... com eterna gratidão ... até sempre!

manuela bairos

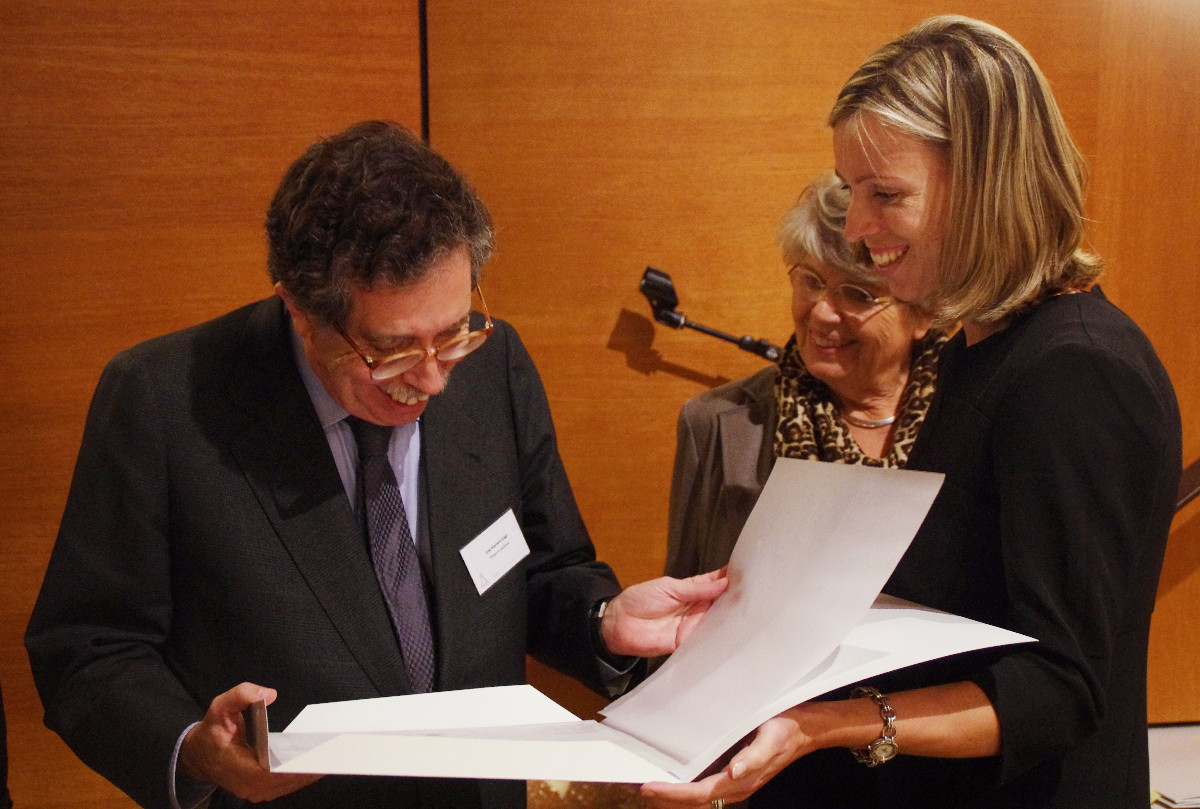

Hovione & MIT Portugal Seminar, 30th June 2014, Lisbon

Showcasing Portuguese Pharma Science - Advances in Discovery, Development and Manufacturing

Panel Discussion: Science Policy & Jobs: Investing in Science for the Future

Panel members: José Mariano Gago

Isabel Pina

Hovione & MIT Portugal Seminar, 30th June 2014, Lisbon

Showcasing Portuguese Pharma Science - Advances in Discovery, Development and Manufacturing

José Mariano Gago assisting to the Seminar

Isabel Pina

Hovione & MIT Portugal Seminar, 30th June 2014, Lisbon

Showcasing Portuguese Pharma Science - Advances in Discovery, Development and Manufacturing

José Mariano Gago and Peter Villax (Hovione)

Isabel Pina

Hovione & MIT Portugal Seminar, 30th June 2014, Lisbon

Showcasing Portuguese Pharma Science - Advances in Discovery, Development and Manufacturing

Panel Discussion: Science Policy & Jobs: Investing in Science for the Future

Moderator: Peter Villax, Hovione

Panel members: José Mariano Gago, PhD, Former Minister of Science & Technology Charles Cooney, PhD, MIT

António Murta, Pathena

Isabel Pina

Hovione & MIT Portugal Seminar, 30th June 2014, Lisbon

Showcasing Portuguese Pharma Science - Advances in Discovery, Development and Manufacturing

Panel Discussion: Science Policy & Jobs: Investing in Science for the Future

Moderator: Peter Villax, Hovione

Panel members: José Mariano Gago, PhD, Former Minister of Science & Technology Charles Cooney, PhD, MIT

António Murta, Pathena

Isabel Pina

José Mariano Gago and European science policy

As the Portuguese Minister for Science and Technology, José Gago was heavily involved in European science policy, such as the agreement on the cooperation with Israel in the Seventh Research Framework Programme. Credit: European Union

Shortly after his appointment as European Commissioner for Research, Science and Innovation, Carlos Moedas had the opportunity to meet with his compatriot, the former long-serving Portuguese Minister for Science and Technology José Mariano Gago. During this meeting, which was very cordial, and at the occasion of a series of further contacts which took place until his death on 17 April 2015, José Gago strove to expose to the new Commissioner his views and concerns about the situation and the future of science in Europe, drawing, for instance, his attention onto a project which he judged worthy to be encouraged and supported by the EU for scientific and political reasons, the SESAME particle accelerator in Jordan.

The former minister was not from the same political side as the current Commissioner. Other persons in his position could have behaved differently, keeping their distance or even waiting for an occasion to criticise. The fact that he chose the opposite attitude reveals a lot about his personality. A seasoned politician, and a very shrewd and skilful one, José Gago was not interested in the political game for its own sake. Politics, in his mind, was nothing more than the only possible way to cause the adoption and implementation of policies able to help reach his objectives as regards what really mattered for him: the advancement of science and the strengthening of this democratic, open, and equitable society he fought for in his country as a student during the last years of the Portuguese authoritarian regime, which was overthrown in April 1974.

An electrical engineer and physicist by training, José Mariano Gago, after a few years in research, shifted to the area of science management and science policy, where he exercised major responsibilities at national level. They culminated in his appointment in 1995 as Minister for Research, a position he held for more than 12 years in four governments. Throughout his mandates, he completed an ambitious programme of reform, modernisation, and internationalisation of the whole Portuguese research and university system, the results of which constitute undoubtedly his major legacy: if Portugal possesses today a modern research and university system, it is largely thanks to him and, in particular, to the very clever and determined way he used in combination the EU Research Framework Programmes and Structural Funds to upgrade the level of Portuguese research laboratories and staff, and fully integrate them in the European science community.

To José Gago, Europe was indeed both the key to the reinforcement of national research systems and a natural dimension of international cooperation. All his life, CERN, the intergovernmental European research organization in particle physics, where he worked as a young researcher, remained for him both a model and a powerful source of inspiration. At the EU level, Gago was instrumental in the launch of the two most important science policy initiatives of the previous decade: he contributed to the adoption of the European Research Area project proposed by Commissioner Philippe Busquin, endorsed in 2000 at the Lisbon European Council at a moment when Portugal held the rotating Presidency of the European Union and as chairman of the Initiative for Science in Europe platform, he campaigned forcefully for the creation of the European Research Council (ERC), the funding agency for basic research at EU level.

Especially interested in issues such as human resources for research, social sciences, the training of scientists, science education, and the public’s knowledge of science, he also fought indefatigably to ensure that such subjects would be addressed by policymakers with the seriousness they deserve. Soon after his appointment as minister, he launched in Portugal a programme aimed at promoting scientific culture called Ciência Viva, which remains today as one of the most long-lasting and successful undertakings of this kind in Europe. A few years before, he had been involved in the preparation of European Week of Scientific Culture, a framework for transnational projects in the field of public understanding of science initiated by the European Commissioner Antonio Ruberti. Later, he would successfully struggle for the inclusion of a substantial programme of socio-economic research in the Fifth EU Research Framework Programme, co-publish a book on the theme of science and schools in Europe, chair the EU High Level Group on Human Resources for Science and Technology which issued the report Europe needs more scientists, and present to the Council of Ministers, together with his colleague from Luxembourg, a series of proposals on scientific careers and mobility of researchers in Europe. Even after he had left the government, José Mariano Gago remained very present in European circles. A sought-after speaker and lecturer, he was a familiar figure at conferences, seminars and workshops, highly appreciated for his broad knowledge and the profundity of his ideas.

Gago’s views on European science policy didn’t coincide completely with those which prevailed in the European institutions. Curiously for someone from a small southern country, he didn’t trust much the European Commission. As it emerges from the preface he wrote to the book The future of Science and Technology in Europe, which stemmed from an informal meeting organized in 2007 at a time when Portugal had again the Presidency of the European Union, in his mind, national governments should be, not only the ultimate deciders in matters of European scientific affairs, but also the major actors in the process of building a scientific Europe. His unease with the European Commission as institution didn’t preclude him, however, from maintaining good relationships with Commission’s people, among whom he counted several close friends.

This real, or apparent, contradiction was not the only one in his life. In private a very warm, kind, attentive and courteous person, extremely perceptive and full of psychological insight, finesse, charm and humour, José Gago could also be sharp in political discussions and was not always the easiest person to work with. Too proud for vulgar boasting, he sometimes couldn’t hide how aware he was of his intellectual power and the value of what he had achieved. This is not uncommon among strong personalities and gifted people, and José Mariano Gago was undoubtedly both. ‘José Mariano’, wrote rightly the Portuguese journalist and political commentator José Victor Malheiros,‘belonged to the very restricted number of persons … unable to speak in public without saying something substantial and interesting, which forces one to think’. Exactly the same could be said about private conversations with him. He was also a true humanist. ‘Happy the country’, wrote Rosalia Vargas, President of Ciência Viva, ‘that has had a minister for science and technology who could talk (at the occasion of a visit to Goa) about Garcia de Orta (referring to a Portuguese Renaissance Jewish physician, herbalist and naturalist who lived in India)’. As a matter of fact, the curiosity of José Gago, an uncommonly erudite and cultivated man, extended far beyond science, even science from past centuries, enabling him to quote the historian Jacob Burckhardt and the novelist Patricia Highsmith in a speech before the European Science Foundation (ESF), or to make observations about the philosophers Bertrand Russell and José Ortega y Gasset in private correspondence.

The unexpected death of José Mariano Gago, who disclosed the cancer he was suffering from only to a limited number of relatives and very close friends, resulted in a wave of vibrant tributes and personal, often moving, testimonies of an impressive magnitude, astonishing even for those who knew how highly appreciated and admired he was. The homage was obviously massive in Portugal, where he is largely considered a hero by the scientific community. But contributions came also from international organizations like UNESCO and OECD, and many from European bodies: CERN, the European Space Agency (ESA), the ESF, the ERC, the European Commission through the voice of Commissioner Moedas, the European Cancer Organization (ECCO), to which he was adviser. Considered together, these comments highlight the major role he played in shaping a series of initiatives in different areas of European scientific cooperation and, maybe above all, in the thinking on European science policy.

Building a true ‘research Europe’ is a long and complex process far from being completed, a collective transgenerational undertaking to which many people contributed: European Commissioners and EU civil servants, scientists, but also national science administrators and ministers for research, some to a particularly remarkable degree. The most outstanding example is the French Hubert Curien, who, in various capacities, has been involved in almost all initiatives of European cooperation in science and technology launched during the past 50 years another one was his colleague Heinz Riesenhuber, whose name is attached to the criteria tailored to identify subjects suitable for funding at European level according to the subsidiarity principle, which dictates that decisions should be taken at the lowest possible level. Both have been ministers for many years. In the Council of Ministers, due to their experience, their reputation, their achievements and their strong European commitment, they were casted as ‘wise men’ to whom everybody listened respectfully. One generation later, José Mariano Gago inherited this role of most senior and famous member of the Council: an often opinionated man, but highly knowledgeable, experienced, intelligent and imaginative. To all participants and observers alike, it was obvious that José Mariano Gago, to borrow an accurate expression used by the Director-General for Research and Innovation Robert-Jan Smits about him, was much more than ‘just another minister’. It is as such that he will be remembered, in Portugal, but also in Europe and European organizations, by all those to whom European science policy matters.

Michel André, former advisor to the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Research and Innovation

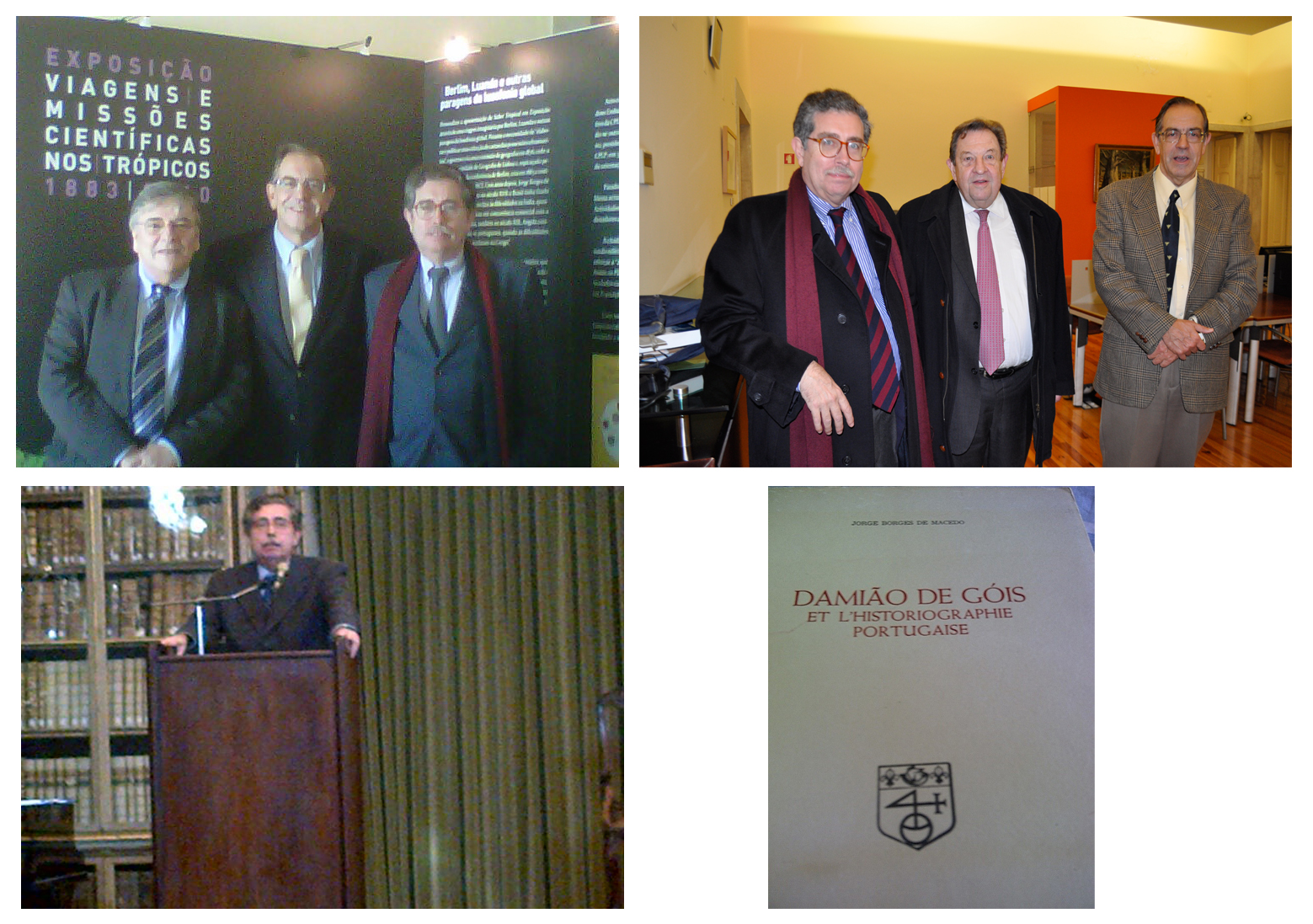

Tribute from the Royal Flemish Academy for Science and the Arts

Brussels, November 15, 2015

Dear family, friends and colleagues of José Mariano Gago,

At the eve of the international conference organized by Manuel Heitor and Rosalia Vargas to foster José Mariano’s legacy, I finally find the strength to leave some words on the overwhelming marianogago.org website. Words to tell you how much we have been in thoughts with him and all of you since we received the terrible news that we would never meet him again.

José Mariano Gago – Thinker-Catalyst in Flanders

We want to take this opportunity to tell you how much the Royal Flemish Academy for Sciences (all sciences) and the Arts and the Flemish education community is indebted to your dear son, father, husband, boss, friend, professor, minister, colleague.

Struck by the lack of scientific literacy and scientific curiosity among the Flemish population – especially amongst the youth – and the unfortunate lack of interest for scientific and technical education and careers, the Academy invited José Mariano Gago to think about this question: “Is Flanders indeed on its way to a knowledge society as promoted by our governmental decision makers?”. In September 2013, after two long meetings at the Academy and many emails, he accepted – in what he called “an act of folly” – the role of Thinker in Residence. He was even more to us than a Thinker, he was a Catalyst for the development of our own thoughts and future actions. He also endowed his “Thinkers in Residence” program with the acronym F2KS for the “Future of Flanders as a Knowledge Society”.

JM valued our initiative, as it rarely happens that the organized scientific community decides to tackle questions of this kind.

José Mariano Gago first asked us to organize face-to-face meetings with important stakeholders in order “to understand” the history and present situation of Flanders as a knowledge society.

To understand! – over and over again he used this verb to explain his ambition and strategy for this new challenge.

His prestige was immense, not only as minister who revolutionized Science and Technology in Portugal but also as great European policy maker, innovating European research together with Commissioner Philippe Busquin. It was often sufficient to name him, to get a private appointment with the busy person we wanted to see.

He carefully chose actors in a broad spectrum of over 30 stakeholders from the most important ministers to the representatives of the Flemish students union.

José Mariano Gago with the Flemish students

These meetings were warm-hearted conversations for all the participants, but also important and influential, by the depth of the exchanged information. I cannot help thinking that every individual felt a richer person after a conversation with José Mariano.

José Mariano Gago – his intellectual testament

He was the architect of the F2KS conference on November 28th 2014, concluding the Thinkers’ program. Five influential and world-known experts on the topic – his friends – twenty Flemish speakers and a great audience made the conference into success. In the final hour of the conference, he conveyed to us all his personal summary on what he learned in Flanders.

His conclusions are a collection of dense and strong thoughts and recommendations – lessons for a future that has already started. We could not guess that this talk was an intellectual testament.

His long and enthusiastic concluding presentation has fortunately been recorded and transcripted, thanks to Bert Seghers, a young mathematician, who left his research position to take the job of project support officer at our Academy, after attending a workshop in which JM gave one of his usual great talks that left the audience amazed and enthusiastic. JM liked him very much.

Today José Mariano’s legacy in Flanders is fostered by different working groups of the Academy. One of them will publish a position paper on STEM-education and STEM-teachers. New research has been done on the figure of Damião de Góis, whom JM refers to in his concluding talk. Thanks to the many conversations, Mariano Gago may have influenced Flemish leaders in their programs being carried out today.

No one has taught us so much, on so many subjects, with such a breadth and depth, and such simplicity and kindness as he did. We shall never forget him.

Irina Veretennicoff and José Mariano Gago in front of the Palace of the Academies in Brussels

Mariano Gago receiving a painting by Panamarenko as a gift from the Academy

With lots of warm regards, saudades and best wishes,

on behalf of the members of the Royal Flemish Academy of Belgium for Sciences and the Arts,

Yours faithfully,

Irina Veretennicoff

Coordinator of the F2KS program

Royal Flemish Academy for Science and the Arts

José Mariano Gago: In memoriam (1948-2015)

.jpg)

Mariano Gago at the 27th FEBS Congress in Lisbon, July 2001, with Joan Guinovart, Claudina Pousada and Julio Celis

José Mariano Gago passed away Friday April 17 after two years with cancer. In spite of the disease, he remained active until the very last day, dealing with daily matters at the Laboratory for Particle Physics (LIP), which he directed, as well as with pressing last minute European science policy issues. Mariano was a remarkable experimental high-energy physicist and a much admired Portuguese political figure, serving two terms in cabinet as Minister of Science and Technology (1995-2002) and Minister of Science, Technology and Higher Education (2005-2011) respectively. He launched the “Ciência Viva” movement in Portugal to promote Science and Technology, reformed higher education, and was one of the most influential science policy makers in Europe during the past decade. With his death, the European scientific community has lost a strong supporter, visionary, and leader.

My friendship with Mariano began in Lisbon, in July 2001 at the 27th Congress of the Federation of European Biochemical Societies (FEBS) organised by Claudina Rodriguez-Pousada. During the Portuguese Presidency of the European Union (EU) in 2000, Mariano was, along with the European Commission (EC), involved in the preparation of the Lisbon Strategy for the European Research Area (ERA), and he was eager to interact with the scientific organisations to build the social constituencies for scientific development. ERA, a vision put forward by former Commissioner Philippe Busquin, placed science at the core of a knowledge-based society, and there was a renewed interest in basic, fundamental research as a means to sustain, on a competitive basis, the conversion of knowledge into tangible economic and social benefits.

At that time, FEBS had already acknowledged the societal responsibility of scientists and invited Mariano to be an adviser to its “Working Group on ERA”. During the deliberations on establishing a European Research Council (ERC) to support basic research of the highest quality, the support from Mariano as Chair of the Initiative for Science in Europe (ISE), a broad-based organisation encompassing all sciences, social sciences and humanities included, and Federico Mayor (Director-General of UNESCO from 1987 to 1999 and chair of the European Research Council Expert Group) was essential in converting the ERC concept into an “object of desire”. When Mariano was reappointed as Minister in 2005, he was instrumental in gaining support from the Council of Ministers for making the ERC a reality. Today, the ERC has become a cornerstone in fulfilling the ambitions of a substantial increase in Europe’s innovativeness and competitiveness.

The European push for a more integrated vision of science in Europe, as well as Mariano’s leadership and political vision prompted the European Cancer Organisation (ECCO) to invite him to become an advisor to their Oncopolicy Committee in 2008. A few years later, when ECCO and other biomedical organisations created the European Alliance for Biomedical Research, Mariano was instrumental in building the concept of a European Council for Health Research (EuCHR), which in Horizon 2020 was translated into the Scientific Panel for Health (SPH). This was achieved in great part thanks to his close collaboration with two of the European Parliament (EP) rapporteurs, MEP Teresa Riera Madurell (PSE group, general rapporteur for the Regulation establishing H2020 and the legal text which is approved by co-decision of the EP and of the Council), and MEP Maria da Graça Carvalho (PPE group, rapporteur for the specific programme). The outcome could be seen as a political landmark for the EP in EU science policy and as a starting point for a stronger cooperation between the EP and European science organisations and societies. Also, for the first time a major political agreement was reached on the need for a comprehensive and long-term scientific strategy to accelerate research and facilitate innovation at EU level.

During the past few months, Mariano spent considerable amount of time advising the European cancer community concerning the creation of Cancer Core Europe, a first step towards establishing a virtual Cancer Institute in Europe. The latter was expected to entice the entire biomedical community into working in unison towards the creation, in the long run, of a European Institute(s) of Health Research.

Mariano´s main scientific activities involved particle physics, a subject that he learned at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) an intergovernmental organisation that he admired and supported both as a scientist and policy maker throughout his scientific career. After spending many years at CERN, Mariano returned to Portugal’s LIP, the institution that he started and led until he died.

Mariano belonged to many organisations. He chaired the International Risk Governance Council (IRGC) in Geneva, and the High-Level Group (HLG) on Human Resources for Science and Technology in Europe. He was a member of the Board of the French National Institute for Health and Medical Research (INSERM), the Board of Trustees of the Cyprus Institute, the Governing Board of Euroscience, and a special advisor to the General Director of the European Space Agency (ESA). He was a member of the Academia Europaea, and an Honorary Member of the European Physical Society.

With Mariano´s death an era has come to an end, and we must work hard to ensure that everything he started will come to a successful end.

Rest in peace, meu Amigo.

Julio E. Celis

Former Secretary General of FEBS, Chair of the Oncopolicy Committee of ECCO

Gostaria de prestar a minha homenagem ao Professor Mariano Gago, investigador internacionalmente reconhecido e activo promotor da ciência e da cultura científica. Como Presidente da JNICT, da FCT e como Ministro lutou sempre, em Portugal mas também a nível Europeu, por um maior investimento em ciência e pela promoção da excelência científica.

O Professor Mariano Gago defendeu desde o primeiro momento nos fóruns europeus a criação do European Research Council, demonstrando uma grande visão e uma profunda compreensão sobre o papel que a Ciência desempenha na construção europeia.

A Europa perdeu um grande cientista. Portugal perdeu um grande homem.

Carlos Moedas, Comissário Europeu da Investigação, Ciência e Inovação

To the family and friends of Mariano Gago:

The passing of Mariano Gago marks a great loss to Portugal, to Europe, to the global community of scholars dedicated to scientific research and education, to me personally, and of course to his family. Mariano and I have been great friends for a long time, as we shared the experience of physicists and academics who, more than once, answered the call to public service. We shared values that celebrated the importance of science, research and education, data-driven analysis, and innovation to the future of our societies. Mariano was an effective promoter of European science and international collaboration. He was also a wonderful person and colleague. We will miss Mariano but also know that all of us - family and friends - are left with a rich store of memories to draw upon for inspiration and good cheer.

Ernie Moniz

Cecil and Ida Green Professor of Physics, MIT (emeritus)

U.S. Secretary of Energy

Ernie Moniz

We feel terribly sorry to hear the sad news of Mr. Gagos passing away. On behalf of both former VM LIU Yanhua and WANG Weizhong, both serving as council members of IRGC, I would like to express our deepest condolence to his family for his passing away and the subsequent great loss to both his family and IRGC. Please also pass on our appreciation of Mr. Gagos valuable contribution to IRGC and the collaboration between China and IRGC. We sincerely hope that his dear family will take care and get recovered soon.

Your sincerely,

WANG Rongfang from MOST, China Director

Division of International Organizations and Conferences

Department of International Cooperation

Ministry of Science and Technology, P.R.China

A morte prematura de José Mariano Gago, porventura o mais inteligente e preparado dos políticos portugueses que conheci, deixou-me imensamente triste. Com o seu falecimento, Portugal perdeu um dos maiores cientistas políticos de sempre, a quem se deve muito da ciência, da história e da cultura portuguesas. Nos últimos anos não houve ninguém tão sabedor como ele nestes domínios, embora a partir do atual governo tivesse sido muito sacrificado, visto não poder atuar como no passado. O seu desaparecimento foi, para todos, uma tristeza infinita.

Excerto da crónica de Mário Soares, in Diário de Notícias, 21-04-2015

A Bright Mind and an Outstanding Policy Maker: A Tribute to José Mariano Gago from the OECD

.jpg)

José Mariano Gago and the OECD Secretary General, Donald. J. Johnston, at the 1999 OECD/CSTP Ministerial Meeting , chaired by Jose Mariano Gago (Portuguese Minister of S&T).

José Mariano Gago opening the OECD Conference “Tertiary Education for the Knowledge Society”, organised in Lisbon in 2008 by the Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education.

With José Mariano Gago, the world has lost a brilliant scientist and outstanding policymaker. He did not just decisively shape the policy landscape in Portugal but his intellectual rigour, charisma and generosity have profoundly influenced the search for better policies in many countries. That is why we were so saddened when we learned that Mariano Gago had passed away on April 17, 2015.

José Mariano Gago was a distinguished particle physicist who prominently contributed to advance the debate on science, technology and higher education policy in Europe. He served as Portugal’s Minister for Science and Technology (1995-2002) and Minister for Science, Technology and Higher Education (2005-2011).

Mariano Gago’s collaboration with the OECD spanned more than two decades, few Ministers have sustained so much dedication and commitment to the international agenda over such a long period. In 1999, he chaired the OECD Committee for Scientific and Technological Policy (CSTP) meeting at Ministerial level which discussed the increased globalisation of R&D and innovative activities. He was an impassioned advocate for Science and Technology (S&T) policy in the OECD, especially on issues of human resources for S&T. But he was also a pioneer of horizontal work, with ideas and approaches that transcended traditional disciplinary boundaries (or Ministries). For example, he had intense interest in policies about the Internet and the digital economy. This translated into Portugal playing a key role on these issues both at the OECD and in other international forums such as ICANN.

Under his leadership, the Portuguese Government launched the “Commitment to Science” initiative to promote public and private investment in science and technology. His period in office as Minister led to the largest growth in modern times in building Portugal’s science base and capacity. The number of full-time researchers per thousand workers grew from 1.5 in the late 80s to 7.2 in 2008 overall R&D expenditure as a proportion of GDP grew from 0.4% in the late 80s to 1.5% in 2008 and business expenditure in R&D as a percentage of GDP grew from 0.2% in the late 90s to 0.76% in 2008. He was a tireless advocate for Portugal, always seeking to leverage its scarce resources by partnering with others such as forging large-scale international collaborations with leading tertiary education research institutions such as Carnegie Mellon University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Mariano Gago also had an admirable interest in making research and technology more accessible and understandable to the general public, as reflected in the 1996 launch of the Ciência Viva (Living Science) programme to promote scientific and technological literacy among the Portuguese population.

Mariano Gago was committed to contributing to the common good and global agenda. But he also knew when was the right moment to bring in the global community to advance the Portuguese agenda. In 2005, he asked the OECD to review tertiary education in Portugal to leverage global experiences with reforming tertiary education systems. And when he reported back to the OECD Education Policy Committee on progress in 2008, delegates from across the OECD were impressed by the breadth and the far-reaching nature of his reforms and, in turn, suggested the Portuguese experience could be useful for reform in other countries. The reform involved encouraging institutions to be more responsive to the needs of society and the economy (with further autonomy for institutions which could opt to become foundations) the creation of a new agency for quality assurance stronger links to employers, regions and labour markets emphasis on making student access more inclusive the extension of the student support system the increase of competitive funding more effective university-industry links for research and innovation and new strategies for internationalisation. Particularly refreshing was Mariano Gago’s concern for combatting elitism in the system and expanding student numbers by embracing new publics.

It was no surprise then that countries asked Portugal to organise the final conference of the OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education, a 3-year project reviewing tertiary education policy in 24 OECD countries, with the launch of the OECD report “Tertiary Education for the Knowledge Society” in Lisbon in 2008. This event brought together the Portuguese tertiary education community and tertiary education policy makers from over 30 OECD countries.

No doubt the success of the implementation of the reform owed a great deal to the remarkable intellectual and operational talents of Mariano Gago. He was particularly skilful at building political support by identifying and targeting key influential individuals and winning them over. He also greatly valued international peer learning as a key element for the successful implementation of the reform.

Mariano Gago’s infectious enthusiasm could be quickly disarming, minutes into a coffee or a beer you quickly found out that you had committed to giving him a special data extraction, attending one his many interesting Conferences or helping a former student of his.

Mariano Gago will be dearly missed not only in his country but also by the international education and research communities, especially at the OECD. His vision and ideas will remain major references for science, technology and higher education policy. And as we say, people never die until they are forgotten.

By Andreas Schleicher, OECD Director for Education and Skills, and

Andrew Wyckoff, OECD Director for Science, Technology and Innovation

José Mariano Gago – personal memories

.jpg)

Photo: Mariano Gago with colleagues and his international expert group for Future of Scientific Culture in Europe, Lisbon, Feb 1995. From left( not all): Svein Sjøberg (N), Harrie Ejkelhof (NL), Bjørn Andersson (S), Mariano Gago (Pt), Vasilis Koulaidis (Greece), Albert C Paulsen (DK), Kurt Riquards (D), Paul Caro (F) and Joan Solomon (UK)

I first got to know Mariano nearly 25 years ago, when he launched the work on a white paper for science education in Europe in the early 1990s.

He had invited a group of science educators and communicators from several European countries to join his group for this work.

We had several productive meeting in and around Lisbon. The final report, Science in Schools and the Future of Scientific Culture in Europe, was published in 1995.

When we had the closing meeting in Estoril, Mariano thanked his international group, and made a final comment: By the way, I have just been appointed as Minister of Education and Research. I have some plans for the future. I hope to work with you on this. Have a safe trip home.

And Mariano was right he had plans! Shortly after taking office as minister, Gago established the first elements of what was to become the most well-known science communication project in Europa: Ciência Viva. I had the pleasure, as one of the handful science educators from other countries to be a member of the international committee. We took part in discussions, gave advice, and also became involved in the evaluation of the progress and development over the years to come.

The cooperation with Mariano also gradually became a personal relationship. In addition to his family, the personal relationship also included Marianos close partners who were recruited to Ciência Viva from the fist years, in particular Rosalia Vargas and Ana Noronha. Rosalia has for a long time been the director of Ciência Viva and in currently also President of Ecsite, The European network of science centers and museums with a total of nearly 400 institutions and organizations.

In 1998, when Expo was arranged in Lisbon, the great Pavillion of Knowledge was opened, and has since then played a majour role as a hub for the impressing portfolio of science communication activities, including the nearly twenty science centers, Centros Ciência Viva, around in Portugal.

From around year 2000 Mariano also became a key person in in the European Union to promote science culture, the term that he so frequently used. The European Commissions high-level group on Human Resources for Science and technology was established after an initiative by Mariano, also to be led by him. The well-known British scientists and expert on the political, social and cultural aspects of science in society, John Ziman, became his close partner in the process of carrying out this work, where the process of engaging various groups and stakeholders was as important as the final product. I had the honour and the pleasure to work with them for two years that this project lasted. The work involved and engaged science unions, universities, industry, labour unions and several interest groups in hearings, conferences etc.

The final product was the report Europe needs more scientists, published in 2004. This report has been instrumental in promoting science and technology education in Europe and its member countries, and has also been a foundation for later initiatives in Europe.

In the following years, up to this year, I had the pleasure of meeting and working with Mariano on several occasions. We met last summer in Cascais, and we met in Brussels on 28th November 2014.

Mariano had at that time worked for some months as Thinker in residence (!) for the Royal Flemish Academy of Belgium for Science and the Arts to give explore and give advice on nothing less than The Future of Flanders as a Knowledge-Based Society, and I was once again invited to contribute to this process.

This work culminated with a conference in Brussels that brought together a large variety of people, representing institutions and organizations that do not often sit around the same table for discussions. He also delivered strongly supported advice – and indeed outspoken critique of current Belgian politics. He seemed to be in excellent shape, and nobody heard anything about any kinds of health problems.

This was to be my last meeting with Mariano, a person I came to appreciate more and more, both as an academic thinker and as a an activist for the place of science in a broad cultural meaning, with a role to play in a modern democracy. Mariano was not only an advocate of science education, research and excellence, but also of social justice and equity.

And, over the years, I also learned to know as an extraordinary warm and caring person, always being interested in the welfare and happiness of other people. He will be remembered – and we will miss him.

Mariano, his daughter Katarina and wife Karin, at the Viking museum, Oslo, 2004

On stage with Rosalia Vargas

Mariano hosting my wife and me for talks in Cascais, last summer, 2014

Mariano Gago, Irina Veretennicoff and Svein Sjøberg, Brussels, Nov 28 2014 Koninklijke Vlaamse Academie van België voor Wetenschappen en Kunsten

Svein Sjøberg, Science educator, University of Oslo, Norway

Homage to José Mariano

José Mariano was an extraordinary person, a person that you simply admire. Another person that I had the privilege to consider a Polar star in my life was Chris Freeman at Sussex.I had the privilege of knowing José Mariano in various roles: minister, scholar, intellectual leader. But I would like to remember him as an extraordinary human being. His smile, his voice, his behavior as a husband (I have rarely seen husbands to be so in love with their wives).

Last year we – the ROARS editorial board – invited José to our annual Conference. His keynote speech was greatly appreciated for his vision, and it inspired the ensuing discussion (https://www.roars.it/online/jose-mariano-gago/). He described the challenges we had, and still have, in front of us, and provided guidance on how to sail in the perilous waves of the European sea.

Photo: José Mariano Gago with part of the the editorial board of ROARS, Rome, 21 February 2014

An anecdote. When José Mariano came to Rome for the 2014 Conference, I picked him up and drove him for a visit to Castelli Romani. He enjoyed very much the archaeological sites like the cistern, the Roman gate and other exhibits.

Photo: José Mariano Gago and Giorgio Sirilli in front of the “Santa Maria della Stella” church, Albano Laziale, 20 February 2014

I was astonished when he, in the Museo of Albano Laziale, looking at a Roman head, discovered that the figure of a young man was asymmetric. He had also a theoretical explanation of this kind of choices made by sculptors in Roman times.

Photo: Head of Tiberius Julius Cesar Gemellus, 29 A.C., Museo Civico Albano Laziale

Later I reported his observation to local archaeologists, who appreciated the finesse of the observer. This episode, along with his way of looking at and commenting on the historical sites and exhibits led me to a conclusion: José was a Renaissance man. He had the rare ability to live with joie de vivre (including love for the cuisine), putting together science and politics, philosophy and history, facing with leggerezza(in Italo Calvino’s sense) the hurdles of life.

Giorgio Sirilli, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche

Nota publicada na Newsletter 95 (2015) da European Mathematical Society (https://www.ems-ph.org/journals/newsletter/pdf/2015-06-96.pdf)

Pedro Freitas

DIETL Monica

Professor Doutor José Mariano Gago no Observatório de Coimbra, no dia 11/08/99 durante um eclipse solar.

Foi com profundo pesar que o Observatório Geofísico e Astronómico soube da morte do Professor Doutor José Mariano Gago, reputado físico a quem a Ciência portuguesa muito deve. E não deve apenas pela sua própria produção científica mas principalmente pelo que ajudou os outros a produzir, através da criação de condições de formação e avaliação segundo padrões internacionais.

Podemos obter inspiração nos versos de Sérgio Godinho quando diz “…toquei-te no ombro e a marca ficou lá …” e dizer do Ministro Mariano Gago que tocou na Ciência Nacional e a marca ficou lá. Ficou e continuará lá. O Ministro Mariano Gago foi ainda um grande impulsionador da Astronomia em Portugal. Se nada mais houvesse (e houve), bastaria apenas referir o seu papel na adesão de Portugal ao Observatório Europeu do Sul.

O Observatório de Coimbra muito deve ao Professor Doutor Mariano Gago. Foi, no seu primeiro mandato, o grande impulsionador de um projecto de digitalização global das imagens solares de Coimbra, para disponibilização às comunidades científica e, em particular, escolar. Com isso, nasceu o projecto “Sol para todos” (www.mat.uc.pt/~sun4all) que hoje em dia leva centenas de alunos e professores em dezenas de países pelo mundo inteiro a olharem para o Sol e a sua actividade de uma forma diferente. Este projecto é um dos inúmeros frutos do programa nacional de divulgação científica, Ciência Viva, que o Ministro Mariano Gago criou e cujo contributo para a compreensão pública da Ciência é de relevância maior.

Guardamos ainda na memória a empenhada visita que o Ministro Mariano Gago fez ao Observatório de Coimbra, em Agosto de 1999, por ocasião de um eclipse solar e da qual deixamos uma singela recordação em forma de homenagem.

O Observatório Geofísico e Astronómico da Universidade de Coimbra apresenta as mais sinceras condolências à família e ao LIP. A Ciência está de luto. Porém, partilhamos da certeza que a comunidade científica nacional frutificará o legado do Professor Doutor José Mariano Gago.

Coimbra, 17 de Abril de 2015

João Fernandes

Sub-Director da Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade de Coimbra para o Observatório Geofísico e Astronómico da Universidade de Coimbra

João Fernandes

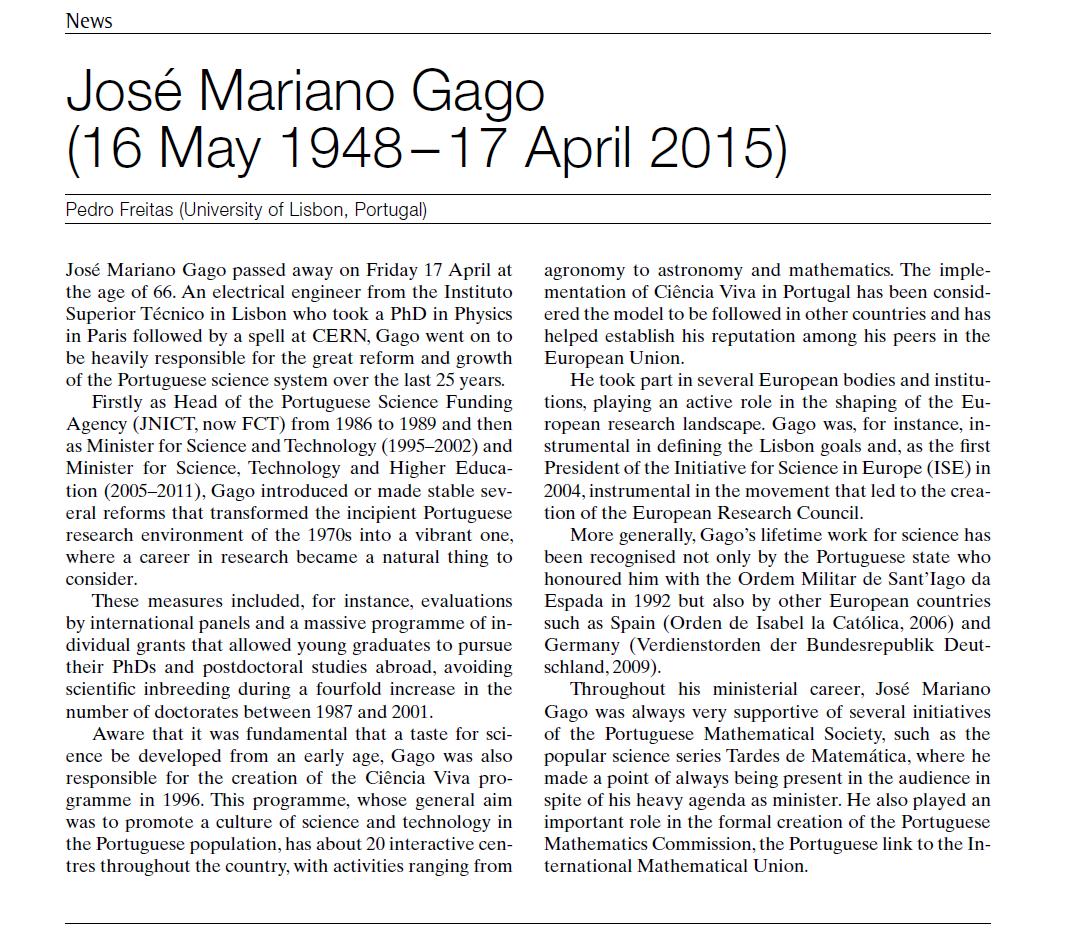

José Mariano Gago 1948-2015

José Mariano Gago, particle physicist and former minister of science in Portugal, passed away on 17 April. He was the person who promoted science in Portugal after the long period of international isolation during the dictatorship that lasted from 1926 to 1974. He was the founder and the present president of the Laboratory for Instrumentation and Experimental Particle Physics (LIP), and was instrumental in Portugals becoming a member state of CERN.

Mariano Gago studied electrical engineering at the Instituto Superior Técnico (1ST) in Lisbon, where he was also involved in continuous political activity, as president of the Students Association. He went on to study for a PhD in particle physics at the École Polytechnique and the Université Pierre et Marie Curie, his thesis being on the Production de H, de et des resonances S* dans les interactions K~-proton à 14.3 GeV/c in an experiment at CERN. He became professor at 1ST in 1978, continuing his involvement with experiments at CERN, to where he regularly returned.

It was at this time that he began to prepare the accession of Portugal to CERN as a full member state. This was finally achieved in 1985. LIP was created some months later, as an institute to bring together a small community of physics researchers coming from different universities. At the same time, he was appointed president of the Portuguese funding agency for science, the Junta Nacional de Investigação Científica e Tecnológica (JNICT). This laid the foundations of an impressive career devoted to the reconstruction and strengthening of the whole of science and technology research in Portugal, which lasted for 30 years

As president of the funding agency, and later as minister, Mariano Gago opened the way to a gigantic increase in the number of people working in science in Portugal. In 25 years, the number of PhD holders increased by a factor of eight. He also imposed new peer-evaluation rules for institutions, fellowships and project grants, leading roles in all areas of science. Thanks to the help of the European Union (EU), which he knew how to make use of in an extremely efficient way, Portuguese science not only increased in size but also improved in quality, and became fully competitive on an international level in many fields.

Mariano Gago believed deeply that science and technology should belong to people in general. During his tenure as minister of science and technology in the years 1995-2002, he created Ciência Viva, a large network of public centres for the popularization of science, extending throughout the country. At the same time, he connected all public schools to the internet, in a pioneering programme. From 2005 to 2011, he was again minister, this time of science, technology and higher education. At 1ST, as a physics professor, he organized nightly particle-physics seminars for all students in the late 1970s, and promoted experimental-physics laboratories for all of the engineering courses in the 1990s.

During the Portuguese EU presidencies, in 2000, Mariano Gago worked with the European Commission to develop the Lisbon Strategy for the European Research Area and the Information Society and, in 2007, he promoted a strategy for the modernization of EU universities. He chairedthe Initiative for Science in Europe, and campaigned for the creation of the European Research Council. He also chaired the High Level Group on Human Resources for Science and Technology, and co-ordinated the European report Europe Needs More Scientists, published in 2004.

He also worked with UNESCO to create Ciência Global, a new initiative for the advanced training of scientists from developing countries. He strongly supported the creation of SESAME - the Synchrotron-light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East - which is bringing together all of the countries in this region, from Israel to Iran, and he ensured that Portugal became an official observer.

Mariano Gago always regarded and quoted CERN as an example of international co-operation and peace, maintaining a constant strong connection with the organization. Many people remember his speech at the inauguration of the LHC, and he wrote recently on his Thoughts on CERNs future, in the context of the 60th-anniversary celebrations (CERN Courier October 2014 p78). He was personally involved in other international scientific organizations, being a special adviser to the director-general of the European Space Agency, and a policy adviser to the European Cancer Organization. He was also a member of the Board of the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research, and was the first president of the International Risk Governance Council in Geneva. He helped to create the Cyprus Institute at Nicosia, and served as a member of its Board of Trustees. He was a member of the Portuguese Academy of Sciences and of the Portuguese Academy of Engineering, as well as of the Academia Europaea.

José Mariano Gago will be remembered for his achievements in many fields, as a particle physicist, a science policy maker, a professor, a dear colleague and, without doubt, a scientist who shaped the scientific culture in his country and internationally.

Gaspar Barreira, LIP

CERN Courier June 2015

Obrigado a Mariano Gago

Ver documento | View document

Intervenção de abertura da Assembleia da SUPERA, Sociedade Portuguesa de Engenharia de Reabilitação e Acessibilidade

Minute of Silence - In honour of Professor M. GAGO, who passed away on 17 April 2015

José Mariano Gago entered particle physics as a young researcher at CERN in the 1970s and went on to become an ardent supporter of the Organization and all that it stands for. He was instrumental in bringing his country, Portugal, to become a Member State of CERN in 1986. He continued to be deeply involved with CERN, twice as a Portuguese Delegate to CERN Council (1985-1990, 2003-2009) and also as the Portuguese Minister of Science and Technology (1995-2002) and then Minister for Higher Education and Science and Technology (2005-2011). His speech as Minister at the LHC Inauguration Ceremony is one that many people still remember.In founding the Laboratory of Instrumentation and Experimental Physics (LIP), created in 1986 under the sponsorship of the National Foundation for Science, José Mariano also set up the basis for the many important contributions that Portuguese physicists and engineers continue to make to CERN and in particular to the exciting adventure of the LHC.

With his passing, the CERN community has lost a dear friend, and a passionate advocate for the importance of science as a bridge for peace in the modern world.

Excerpt Bulletin, 18 June 2015

Agniezka Zalewska, President of CERN Council

Letter to Jose Mariano Gago

Dear Jose

We met twice. The first time was in The Netherlands were you were invited as a speaker at a colloquium on the topic “Europe needs more scientists”. You made a profound impression with your vision on this topic, but even more with your Ciencia Viva project. Listening to you I got the feeling, that YES it is possible to enthuse teachers and their pupils for science and technology. By providing a considerable amount of time and resources (no surprise there) and put them in the hands of an empowering leader. And that is how I perceived you at that time.

We met again several years later in the Thinkers Program of the Royal Flemish Academy for Sciences and the Arts. I was truly honored to be invited to participate in this project. But more than anything else, I was very happy to get the occasion to discuss with you. You have your way of putting people at ease, comforting them, so they dare to tell sincerely what they have in mind. You listen very patiently, distill the crucial points and connect them with your own insight and experience into a coherent picture. Such is a gift that I very much envy. I can tell you that each time we met, I got a better grip on my own ideas, a clearer view on where I want to go and steer RVO-Society.

I had no idea that you had to leave us so soon. There are so many issues I would have loved to discuss with you. Hours of passionate debate I was looking forward to. They will be no more, and that hurts. You are truly a unique person, a passionate scientist, a cautious leader, an empowering friend. I will miss you and so will we all at RVO-Society. But rest assured, we will never forget you. Thank you so much.

Jo Decuyper, RVO-Society

Reflectindo sobre Mariano Gago, a Ciência e a Família - Revisitação do artigo publicado no Público

Foi quem introduziu em Portugal o moderno paradigma da Política da Ciência, através da orientação que deu, a partir de 1986, recém-nomeado Presidente da Junta Nacional da Investigação Científica e Tecnológica (JNICT). E pelos organismos que se propôs criar e do processo que iniciou com o Programa Mobilizador, em 1987, que conduziu para que com todo o rigor fossem plenamente aproveitados os fundos europeus e nacionais para o desenvolvimento da ciência em Portugal.Era uma pessoa que via longe e com um pensamento inovador. Enquanto muitos responsáveis continuavam a ver o país como em vias de desenvolvimento, ele vê-o já como país industrializado. Nessa mesma altura as Nações Unidas integram Portugal no grupo dos países industrializados. Enquanto muitos responsáveis tinham ainda na cabeça um modelo de mudança tecnológica já desacreditado e posto de lado, vendo-o como a sucessão investigação fundamental-investigação aplicada-desenvolvimento tecnológico e daí a inovação, ele tinha a ideia que era um processo muito mais complexo. Conjugando as duas perspectivas erróneas, muitos responsáveis preconizavam políticas paternalistas e redutoras dando primazia à investigação aplicada. Quando no entanto, por exemplo, nas Ciências da Saúde se faz investigação para produzir um medicamento ou um tratamento é hoje frequente ter de haver investigação fundamental de ponta como em Biologia Molecular. O enfoque é no produto, o qual determina o tipo de investigação requerida. Mariano Gago ironizava: “Investigação aplicada, teremos de ver é se é aplicável”. E sabia também como o conhecimento científico cria oportunidades. Por exemplo, foram descobertas no domínio da Física que conduziram à fibra óptica, de tão grande importância nas comunicações.

Dava ainda grande importância à inovação, pelo que propôs a criação da Agência da Inovação, organismo que com as dificuldades burocráticas e de procedimentos legislativos só veio a ser estabelecido mais tarde.

Vendo a ciência como uma base essencial do progresso, preocupavam-no a dificuldade de nosso país se levar até ao fim projectos, pela instabilidade e descontinuidade de fundos. Indo buscar num sentido literal expressões vindas da sua formação inicial em Engenharia Electrotécnica, dizia que as políticas científicas em Portugal funcionam em regime de corrente alterna, pelo que temos de as pôr a funcionar em regime de corrente contínua.

Em meados de 1989, encontrei-o em Paris num acontecimento da UNESCO, em que viemos a partilhar um jantar, depois do qual fizemos uma longa caminhada pelo Quartier Latin e tivemos uma longa conversa na qual me disse que pensava há algum tempo falar comigo para me explicar as temáticas e pontos da sua orientação para a política científica. Eu estava na altura na Universidade de Manchester e tinha lido muita coisa da literatura em política da ciência, sociologia da ciência e economia da inovação. Tomei consciência que essas questões eram enquadráveis em importantes aspectos teóricos e nas agendas de investigação nessas matérias. Esta conversa foi central para a minha tese, a qual veio a ser reconhecida.

Pelo seu mérito como cientista reconhecido, foi nomeado num alto posto num governo PSD e ministro em governos PS que lhe sucederam. Em ambos os cargos acolheu e mobilizou investigadores de todas as correntes partidárias e ideológicas, estabelecendo consensos, o que proporcionou o sucesso das acções de desenvolvimento do sistema de C&T.

Em 1995, num governo PS conseguiu haver pela primeira vez no país um ministério dedicado à ciência que incluiu as novas tecnologias da informação, o Ministério da Ciência e da Tecnologia, do qual foi o titular. Na delimitação do âmbito ministerial, desde início achou que a ciência e a inovação deveriam estar próximas, para se poder induzir o seu aproveitamento. Sem ser a totalidade e sem estar na designação do ministério teve a seu cargo, desde o primeiro ao último governo em que participou, uma parte muito importante da inovação. E desde início também achava importante integrar o ensino superior no mesmo ministério que a ciência. Mas na altura não houve condições. De facto, na fase actual o sector ensino superior é uma “fábrica” no sentido mais profundo de produção de novo conhecimento científico, de transferência de conhecimento para os utilizadores quer sejam da administração pública, da cultura ou das empresas e de difusão do conhecimento pelo ensino. A partir de 2005, o ministério que tutelou abrangeu o ensino superior. Nos governos PSD anteriores tinha havido essa junção e num deles, de breve duração, foi incluída a inovação.

Hoje, voltar a inserir o ensino superior na Educação foi um retrocesso assim como aí integrar a ciência, quando em Portugal desde o final dos anos 60 se procurou que a coordenação e o financiamento das actividades de investigação científica estivessem inseridos na orgânica governativa de forma a poderem apoiar todos os sectores (laboratórios de estado, universidades, instituições privadas sem fins lucrativos e empresas). O organismo de formulação e gestão da política científica nunca esteve no ministério da educação.

A sua grande generosidade proporcionou-me conhecer a sua família, a mulher reconhecida cientista social especializada em sociologia da família a filha hoje também académica e investigadora como os pais o pai advogado já falecido, nascido no Algarve, e a mãe, que na juventude desenvolveu intensa actividade de voluntariado social e apaixonada por música, levando o Zé desde pequeno aos concertos na Gulbenkian.

Num dia em que em Lisboa se realizaria um congresso científico e à noite o jantar do congresso, por coincidência, no Instituto Francês haveria um colóquio em que Mariano Gago participaria. Decidi assistir a este acontecimento. Na altura vivia na linha de Sintra. Ao entrar no Instituto e vendo-me, disse-me para esperar por ele no final da sessão pois ao ir para casa me deixaria na estação. Quando íamos a sair, veio uma pessoa do congresso pedir-lhe insistentemente que fosse ao jantar, ao que respondeu não poder. Pelo caminho explicou-me que tinha dito à filha que lhe faria companhia ao jantar e queria cumprir o que lhe prometera.

Com a minha vida atribulada, perdi a ligação com o Zé Mariano e a sua família. Apesar de terem passado muitos anos, na memória vejo sempre os Gago como uma família afectiva.

E como muitos comentadores têm dito, a melhor homenagem a Mariano Gago é prosseguir a sua acção. Desta vez deveria ser criado um Ministério da Ciência, da Inovação e do Ensino Superior. E continuar o apoio ao desenvolvimento do sistema científico, pois que nenhum corpo pode funcionar sem ser continuadamente alimentado.

Beatriz Ruivo

Doutorada em Política de Ciência e Tecnologia pela Universidade de Manchester (1991). Foi Professora Associada na Universidade de Aveiro, onde lançou e coordenou o Mestrado em Gestão de Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação, e Secretária do Comité de Investigação em Sociologia da Ciência e Tecnologia da Associação Internacional de Sociologia.

Obrigado por ter acreditado em mim!

Maria Odette Santos Ferreira, Faculdade de Farmácia da Universidade de Lisboa

José Mariano Gago 1948–2015

.jpg)

CERN Courier Jun 2, 2015

José Mariano Gago, particle physicist and former minister of science in Portugal, passed away on 17 April. He was the person who promoted science in Portugal after the long period of international isolation during the dictatorship that lasted from 1926 to 1974. He was the founder and the present president of the Laboratory for Instrumentation and Experimental Particle Physics (LIP), and was instrumental in Portugal’s becoming a member state of CERN.

Mariano Gago studied electrical engineering at the Instituto Superior Técnico (IST) in Lisbon, where he was also involved in continuous political activity, as president of the Students’ Association. He went on to study for a PhD in particle physics at the École Polytechnique and the Université Pierre et Marie Curie, his thesis being on the Production de Ξ–, de Ω– et des resonances Ξ* dans les interactions K–-proton à 14.3 GeV/c in an experiment at CERN. He became professor at IST in 1978, continuing his involvement with experiments at CERN, to where he regularly returned.

It was at this time that he began to prepare the accession of Portugal to CERN as a full member state. This was finally achieved in 1985. LIP was created some months later, as an institute to bring together a small community of physics researchers coming from different universities. At the same time, he was appointed president of the Portuguese funding agency for science, the Junta Nacional de Investigação Científica e Tecnológica (JNICT). This laid the foundations of an impressive career devoted to the reconstruction and strengthening of the whole of science and technology research in Portugal, which lasted for 30 years.

As president of the funding agency, and later as minister, Mariano Gago opened the way to a gigantic increase in the number of people working in science in Portugal. In 25 years, the number of PhD holders increased by a factor of eight. He also imposed new peer-evaluation rules for institutions, fellowships and project grants, opening the way for a new generation of people to take leading roles in all areas of science. Thanks to the help of the European Union (EU), which he knew how to make use of in an extremely efficient way, Portuguese science not only increased in size but also improved in quality, and became fully competitive on an international level in many fields.

Mariano Gago believed deeply that science and technology should belong to people in general. During his tenure as minister of science and technology in the years 1995–2002, he created Ciência Viva, a large network of public centres for the popularization of science, extending throughout the country. At the same time, he connected all public schools to the internet, in a pioneering programme. From 2005 to 2011, he was again minister, this time of science, technology and higher education. At IST, as a physics professor, he organized nightly particle-physics seminars for all students in the late 1970s, and promoted experimental-physics laboratories for all of the engineering courses in the 1990s.

During the Portuguese EU presidencies, in 2000, Mariano Gago worked with the European Commission to develop the Lisbon Strategy for the European Research Area and the Information Society and, in 2007, he promoted a strategy for the modernization of EU universities. He chaired the Initiative for Science in Europe, and campaigned for the creation of the European Research Council. He also chaired the High Level Group on Human Resources for Science and Technology, and co-ordinated the European report Europe Needs More Scientists, published in 2004.

He also worked with UNESCO to create Ciência Global, a new initiative for the advanced training of scientists from developing countries. He strongly supported the creation of SESAME – the Synchrotron-light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East – which is bringing together all of the countries in this region, from Israel to Iran, and he ensured that Portugal became an official observer.

Mariano Gago always regarded and quoted CERN as an example of international co-operation and peace, maintaining a constant strong connection with the organization. Many people remember his speech at the inauguration of the LHC, and he wrote recently on his Thoughts on CERN’s future, in the context of the 60th-anniversary celebrations (CERN Courier October 2014 p78). He was personally involved in other international scientific organizations, being a special adviser to the director-general of the European Space Agency, and a policy adviser to the European Cancer Organization. He was also a member of the Board of the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research, and was the first president of the International Risk Governance Council in Geneva. He helped to create the Cyprus Institute at Nicosia, and served as a member of its Board of Trustees. He was a member of the Portuguese Academy of Sciences and of the Portuguese Academy of Engineering, as well as of the Academia Europaea.

José Mariano Gago will be remembered for his achievements in many fields, as a particle physicist, a science policy maker, a professor, a dear colleague and, without doubt, a scientist who shaped the scientific culture in his country and internationally.

Gaspar Barreira, Laboratório de Instrumentação e Física Experimental de Partículas (LIP)

"José Mariano Gago, estudante e dirigente associativo". Entrevista a José Mariano Gago por Luísa Tiago de Oliveira, feita a 07/11/2010

Ver documento | View document

Entrevista foi feita no quadro do projecto "IST. Um Século de Existência. Cultura, Técnica e Sociedade", PTDC/ANT/65979/2006, financiado pela FCT e pelo IST.

I met Professor Mariano Gago for the first time at a conference in Lisbon, when called for his help with my master’s dissertation on the topic of discourse in science communication. Here we have something that really interests me, he replied. 20 years later I still recall from that day his generosity, wisdom and humanity.

In May 1996 we launched Ciência Viva. I immediately grasped the scale of the task, but, for a moment, I feared my ability to carry it out. Why did you choose me, Professor? Because you have the ability to learn. Because the scientific community will help you. Because parents and teachers have been expecting this for a long time. Because school kids deserve it.

And I learned. I did it during formal meetings for which he gathered people from many different areas - even those unlikely for a politician’s office - and also during visits to bookstores (new and old second hand ones), where our discussions crossed the path of books he admired, searched for and discovered. I quickly realised that my learning would have to go beyond the reports, studies, essays and international publications that I needed to know. And from a bookshelf Blue August would jump out, while Manuel Ferreira Gomes inspired a conversation about literature and politics. He gave me that book, and whenever I touch or recall it, I realize the man of letters, of sciences and of the world he was at all times.

I learned with him that politics have a soul, that you have to listen, as he did at every meeting: he literally listened, listened a lot and only then did he speak, making everything seem natural and simple, even what was new and difficult to grasp. A minister who would sit on the edge of the stage to get closer to the audience, who talked about what things are made of, with an erudition steaming from much literature.

To accompany him on official visits was a constant source of learning and a cause of pride. In a tiny notebook that easily fitted in his pocket, he would improvise the most touching speeches. I never heard a circumstantial speech from him.

We were very lucky to have a scientist, a politician and a democrat, all together in the same person. For people, like us, who believe in the appropriation of science by the largest number, he made it all look easier. We didn’t have to waste our time persuading a policy-maker about the key role of scientific culture in modern societies.

Quite the opposite, it would be himself who would tell us all the time:

You must fight scientific illiteracy.

Work with the teachers in their schools.

Open the labs’ doors to people and let them know our researchers, where they work and what results they are achieving.

Build science centres, many science centres, all over the country.

Take science to people.

Bring people to science.

Pick up your telescopes and your scientific instruments, go out and meet people, on the beaches and on the mountains, in the cities and in the countryside.

Tell me: what do you need to accomplish this? Let me know what is needed and I shall place the resources of this country at the service of science, science education and of scientific culture. And so he did, day after day, until the very last day of his life.

Ciência Viva was one of the instruments by which he did this: “To promote scientific culture is Ciência Viva’s major challenge, one that it shows and debates today, as a key contribution for citizenship.” These were the words he used to conclude his opening speech of the first Ciência Viva Forum in 1997. Because, in his words, without thought, without a structured dialogue on the why of things, without controversy, without enigma, without true experimentation, there is no science nor scientific education.

Of the regulations and necessary instruments he always asked that they be simple and clear, so contrary to bureaucracy thwarting the more creative processes, regulations rooted in doing and appropriated by those who had been longing for them for a long time: the schoolteachers.

In fact, in the context of the political changes that Portuguese society was going through, Ciência Viva responded to the urgency of an intervention, guided towards the improvement of practical work and inquiry-based learning of science. The success of this initiative was due both to a project-oriented culture and an unshakable reliance in the capacity of the teachers. Believing in that capacity, making them accountable for their projects’ outcomes, was the key to an emergent social movement for science, particularly in schools. There is, today, a Ciência Viva generation: Mafalda Lapa, a secondary education biology teacher talks about a minister who, being a minister of science, changed education itself. “

All across Portugal, the expression of this social movement for science took the form of a call for the creation of science-dedicated spaces for public use. And that was how Ciência Viva centres popped-up throughout the country, within a growing network, providing space for scientific culture but also for the mobilization of the more dynamic local agents, in economic, social and cultural terms.

On www.marianogago.org website it is possible to find a wide range of testimonies from people who had contact with him at some point in their lives: whether in Portugal or abroad, in a school for small children or for grown-ups, elementary school teachers or university teachers, large institutions or small civil society associations. It is indeed an infinite page – as in the words of our Nobel Prize winner for literature, José Saramago, when referring to the Internet. A democratic page that publishes testimonies from all those who wish to do so, from anywhere in the world. An infinite page, contrary to our ability to express the great sadness for the premature departure of a personality the country owes so much to, while at the same time expressing the joy we feel for the huge legacy he left us.

No one knows enough to do everything by themselves. I cannot remember how many times I heard him say this. That is why he sent us out to learn from other people, both in Portugal and abroad. It is therefore no wonder that our strategic position reached an unprecedented international dimension, consolidating international contact networks, strengthened over a period of two decades. It is a happy country that has had a minister for science and technology who could talk about Garcia de Orta, like on that visit to Goa, where he created all the bridges, the knowledge always being the biggest.

Time is never enough, neither for speaking nor for listening. I also heard him say this many times, as if calling on each one of us to save time, as slow and reflected upon as possible, in order to become more wise and lucid.

But there are other sentences, beautiful and simple, that showed us the greatness of his acceptance of the human condition, expecting the best from each and every one: We cannot make people out of clay, like a potter.

This is my testimony, at a time when the pain of departure still overrides the joy of arrival. Of the arrival of the 20 years of Ciência Viva. And when I talked with him about this celebration, that is coming next year, he said: create a living archive, save and record the memory, like historians and social scientists do, but celebrate it with your eyes in the future, in a prospective way. Where do we want to be in the next 20 years?

Sometimes he was in a hurry and today we know why. He left, much too early.

(published in Jornal de Letras, 2015/04/29)

Rosalia Vargas, President of Ciência Viva

Last month we lost a fine man, a dear friend. We lost Mariano. It took me several days to overcome the shock. Because we became poorer at a time of great needs. When gifted are rare. All who knew Mariano will understand his unique personality: a prominent scientist, a gifted educator, a passionate but rational reformer. He was a pioneer in promoting science and scientific culture not only in Portugal but all over Europe. He had a vision and he managed articulated it. He was dedicated to innovative ideas but more importantly he had the passion to implement them. He invented solutions, if he did not find any, and he had great resilience on this by never giving up. Mariano found ways to overcome the forces of inertia which neutralize efforts of changes. And he was fair and direct, gentle but insistent, strict sometimes but generous. And when criticizing, his sense of humor softened the edges of action. He was a loyal friend, warm and trusting. He had the talent to reach and discover people where they were. Mariano, all of us who were lucky enough to meet you and work with you, we want you to know that you left us the best legacy. Mariano, we will miss you dearly. Farewell my good friend.

Vasilis Koulaidis, University of Peloponnese, Greece

I was shocked and really saddened to learn about José Mariano’s passing away. On the Euroscience homepage, Peter Tindemans has written an excellent obituary focussed on his personal recollections ( https://www.euroscience.org/news/in-memory-of-jose-mariano-gago/ ). Ive participated in many of the meetings and discussions, he mentions (the UNESCO meeting in Paris, ESOF in Barcelona, the ISE discussions, etc.) and remember well, how José Mariano was a driving force in the discussions.

I met José Mariano for the first time a few years before his first term as a minister. His mission at that time: Public understanding of science, one of his great passions and our (common) task at hand in the mid-1990s was to fill the new-born European Science Weeks with life. Ten years later, in an interview given to RTD info in 2005, he expressed this very eloquently: “The sharing of knowledge is quite simply a question of democracy and even of justice ...” The statement encapsulates José Mariano’s thinking. He saw science as part of a much larger picture. But he also saw the bigger picture of science itself.

I also remember long personal, if infrequent, conversations with José Mariano.